Music of Russia

| Music of Russia | ||||||||

| Genres | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Specific forms | ||||||||

|

||||||||

| Media and performance | ||||||||

|

||||||||

| Nationalistic and patriotic songs | ||||||||

|

||||||||

| Regional music | ||||||||

|

||||||||

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Russia |

|---|

|

| Society |

| Topics |

| Symbols |

Music of Russia denotes music produced from Russia and/or by Russians. Russia is a large and culturally diverse country, with many ethnic groups, each with their own locally developed music. Russian music also includes significant contributions from ethnic minorities, who populated the Russian Empire, the Soviet Union and modern-day Russia. Russian music went through a long history, beginning with ritual folk songs and the sacred music of the Russian Orthodox Church. The 19th century saw the rise of highly acclaimed Russian classical music, and in the 20th century major contributions by various composers such as Igor Stravinsky as well as Soviet composers, while the modern styles of Russian popular music developed, including Russian rock, Russian hip hop and Russian pop.

History

[edit]Early history

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (December 2009) |

Written documents exist that describe the musical culture of the Rus'. The most popular kind of instruments in medieval Russia were thought to have been string instruments, such as the gusli or gudok. Archeologists have uncovered examples of these instruments in the Novgorod region dating as early as 11th century.[1] (Novgorod republic had deep traditions in music; its most popular folk hero and the chief character of several epics was Sadko, a gusli player). Other instruments in common use include flutes (svirel), and percussive instruments such as the treshchotka and the buben. The most popular form of music, however was singing. Bylinas (epic ballads) about folk heroes such as Sadko, Ilya Muromets, and others were often sung, sometimes to instrumental accompaniment. The texts of some of these epics have been recorded.

In the time the Tsardom of Russia, two major genres formed Russian music: the sacred music of the Orthodox Church and secular music used for entertainment. The sacred music draws its tradition from the Byzantine Empire, with key elements being used in Russian Orthodox bell ringing, as well as choral singing. Neumes were developed for musical notation, and as a result several examples of medieval sacred music have survived to this day, among them two stichera composed by Tsar Ivan IV[2] in the 16th century.

Secular music included the use of musical instruments such as fipple flutes and string instruments, and was usually played on holidays initially by skomorokhs – jesters and minstrels who entertained the nobility. During the reactionary period of the Great Russian Schism in the 17th century, skomorokhs along with their form of secular music were banned from plying their trade numerous times, their instruments were burned and those who disagree with Alexis of Russia's 1648 law "About the correction of morals and the destruction of superstitions" (Об исправлении нравов и уничтожении суеверий) were punished physically first and then were to be deported to Malorossia (modern Ukraine), but despite these restrictions, some of their traditions survived to the present day.[3][4][5]

18th and 19th century: Russian classical music

[edit]

Russia was a late starter in developing a native tradition of classical music due to its geographic remoteness from Western Europe and the proscription by the Orthodox Church against secular music.[6] Beginning in the reign of Ivan IV, the Imperial Court invited Western composers and musicians to fill this void. By the time of Peter I, these artists were a regular fixture at Court.[7] While not personally inclined toward music, Peter saw European music as a mark of civilization and a way of Westernizing the country; his establishment of the Western-style city of Saint Petersburg helped foster its spread to the rest of the upper classes.[8] A craze for Italian opera at Court during the reigns of Empresses Elisabeth and Catherine also helped spread interest in Western music among the aristocracy.[9] This craze became so pervasive that many were not even aware that Russian composers existed.[10]

The focus on European music meant that Russian composers had to write in Western style if they wanted their compositions to be performed. Their success at this was variable due to a lack of familiarity with European rules of composition. Some composers were able to travel abroad for training, usually to Italy, and learned to compose vocal and instrumental works in the Italian Classical tradition popular in the day. These include ethnic Ukrainian composers Dmitri Bortniansky, Maksim Berezovsky and Artem Vedel.[11]

The first great Russian composer to exploit native Russian music traditions into the realm of secular music was Mikhail Glinka (1804–1857), who composed the early Russian language operas Ivan Susanin and Ruslan and Lyudmila. They were neither the first operas in the Russian language nor the first by a Russian, but they gained fame for relying on distinctively Russian tunes and themes and being in the vernacular.

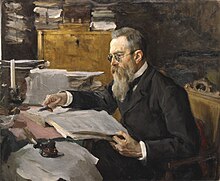

Russian folk music became the primary source for the younger generation composers. A group that called itself "The Mighty Five", headed by Balakirev (1837–1910) and including Rimsky-Korsakov (1844–1908), Mussorgsky (1839–81), Borodin (1833–87) and César Cui (1835–1918), proclaimed its purpose to compose and popularize Russian national traditions in classical music. Among the Mighty Five's most notable compositions were the operas The Snow Maiden (Snegurochka), Sadko, Boris Godunov, Prince Igor, Khovanshchina, and symphonic suite Scheherazade. Many of the works by Glinka and the Mighty Five were based on Russian history, folk tales and literature, and are regarded as masterpieces of romantic nationalism in music.

This period also saw the foundation of the Russian Musical Society (RMS) in 1859, led by composer-pianists Anton (1829–94) and Nikolay Rubinstein (1835–81). The Mighty Five was often presented as the Russian Music Society's rival, with the Five embracing their Russian national identity and the RMS being musically more conservative. However the RMS founded Russia's first Conservatories in St Petersburg and in Moscow: the former trained the great Russian composer Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky (1840–93), best known for ballets like Swan Lake, Sleeping Beauty, and The Nutcracker. He remains Russia's best-known composer outside Russia. Easily the most famous successor in his style is Sergei Rachmaninoff (1873–1943), who studied at the Moscow Conservatory (where Tchaikovsky himself taught).

The late 19th and early 20th century saw the third wave of Russian classics: Igor Stravinsky (1882–1971), Alexander Scriabin (1872–1915), Sergei Prokofiev (1891–1953) and Dmitri Shostakovich (1906–1975). They were experimental in style and musical language. Stravinsky was particularly influential on his contemporaries and subsequent generations of composers, both in Russia and across Europe and the United States. Stravinsky permanently emigrated after the Russian revolution. Although Prokofiev also left Russia in 1918, he eventually returned and contributed to Soviet music.

In the late 19th to early 20th centuries, the so-called "romance songs" became very popular. The greatest and most popular singers of the "romances" usually sang in operas at the same time. The most popular was Fyodor Shalyapin. Singers usually composed music and wrote the lyrics, as did Alexander Vertinsky, Konstantin Sokolsky, and Pyotr Leshchenko.

20th century: Soviet music

[edit]

After the Russian Revolution, Russian music changed dramatically. The early 1920s were the era of avant-garde experiments, inspired by the "revolutionary spirit" of the era. New trends in music (like music based on synthetic chords) were proposed by enthusiastic clubs such as Association for Contemporary Music.[12] Arseny Avraamov pioneered the graphical sound, and Leon Theremin invented thereminvox, one of the early electronic instruments.

However, in the 1930s, under the regime of Joseph Stalin, music was forced to be contained within certain boundaries of content and innovation. Classicism was favoured, and experimentation discouraged.[13] (A notable example: Shostakovich's veristic opera Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District was denounced in Pravda newspaper as "formalism" and soon removed from theatres for years).

The musical patriarchs of the era were Sergei Prokofiev, Dmitri Shostakovich, Aram Khachaturian and Alexander Alexandrov. The latter is best known for composing the Anthem of the Soviet Union and the song "The Sacred War". With time, a wave of younger Soviet composers, such as Georgy Sviridov, Alfred Schnittke, and Sofia Gubaidulina took the forefront due to the rigorous Soviet education system.[12] The Union of Soviet Composers was established in 1932 and became the major regulatory body for Soviet music.

Jazz was introduced to Soviet audiences by Valentin Parnakh in the 1920s. Singer Leonid Uteosov and film score composer Isaak Dunayevsky helped its popularity, especially with the popular comedy movie Jolly Fellows, which featured a jazz soundtrack. Eddie Rosner, Oleg Lundstrem and others contributed to Soviet jazz music.

Film soundtracks produced a significant part of popular Soviet/Russian songs of the time, as well as of orchestral and experimental music. The 1930s saw Prokofiev's scores for Sergei Eisenstein's epic movies, and also soundtracks by Isaak Dunayevsky that ranged from classical pieces to popular jazz. Notable film composers from the late Soviet era included Vladimir Dashkevich, Tikhon Khrennikov, Alexander Zatsepin, and Gennady Gladkov, among others.

| External videos | |

|---|---|

Among the notable people of Soviet electronic music were Vyacheslav Mescherin, creator of Electronic Instruments Orchestra, and ambient composer Eduard Artemiev, best known for his scores for Andrei Tarkovsky's films Solaris, Mirror, and Stalker.

The 1960s and 1970s saw the beginning of modern Russian pop and rock music. It started with the wave of VIAs (vocal-instrumental ensembles), a specific sort of music bands performing radio-friendly pop, rock and folk, composed by members of the Union of Composers and approved by censorship. This wave begun with Pojuschie Gitary and Pesnyary; popular VIA bands also included Tcvety, Zemlyane and Verasy. That period of music also saw individual pop stars such as Iosif Kobzon, Sofia Rotaru, Alla Pugacheva, Valery Leontiev, Yuri Antonov. Many of them remain popular to this day. They were the mainstream of Soviet music media, headliners of festivals such as Song of the Year, Sopot, and Golden Orpheus. The year 1977 saw also establishment of Moskovsky Komsomolets hit parade, the Russia's first music chart.

Music publishing and promotion in the Soviet Union was a state monopoly. To earn money and fame from their talent, Soviet musicians had to assign to the state-owned label Melodiya. This meant accepting certain boundaries of experimentation, that is, the family-friendly performance and politically neutral lyrics favoured by censors. Meanwhile, with the arrival of new sound recording technologies, it became possible for common fans to record and exchange their music via magnetic tape recorders. This helped underground music subculture (such as bard and rock music) to flourish despite being ignored by the state-owned media.[14]

"Bardic" or "authors' song" (авторская песня) is an umbrella term for the singer-songwriter movement that arose at the early 1960s. It can be compared to the American folk revival movement of the 60s, with their simple single-guitar arrangements and poetical lyrics. Initially ignored by the state media, bards like Vladimir Vysotsky, Bulat Okudzhava, Alexander Galich gained so much popularity that they finished being distributed by the state owned Melodiya record company. The largest festival of bard music is Grushinsky festival, held annually since 1968.

Rock music came to the Soviet Union in the late 1960s with Beatlemania, and many rock bands arose during the late 1970s, such as Mashina Vremeni, Aquarium, and Autograph. Unlike the VIAs, these bands were not allowed to publish their music, and remained underground. The "golden age" of Russian rock is widely considered to have been the 1980s. Censorship was mitigated, rock clubs opened in Leningrad and Moscow, and soon rock became mainstream.[15] Popular bands of that time include Kino, Alisa, Aria, DDT, Nautilus Pompilius, and Grazhdanskaya Oborona. New wave and post-punk were the trend in 80s Russian rock.[14] Soviet and Russian conservatories have turned out generations of world-renowned soloists. Among the best known are violinists David Oistrakh and Gidon Kremer,[16][17] cellist Mstislav Rostropovich,[18] pianists Vladimir Horowitz,[19] Sviatoslav Richter,[20] and Emil Gilels,[21] and vocalist Galina Vishnevskaya.[22]

21st century: modern Russian music

[edit]

Russian pop music is well developed, and enjoys mainstream success via pop music media such as MTV Russia, Muz TV and various radio stations. Right after the fall of the Iron Wall, artists, like Christian Ray, took an active political stance, supporting the first president Boris Yeltsin. A number of pop artists have broken through in recent years. The Russian duet t.A.T.u. is the most successful Russian pop band of its time. They have reached number one in many countries around the world with several of their singles and albums. Other popular artists include the Eurovision 2008 winner Dima Bilan, as well as Valery Meladze, Grigory Leps, VIA Gra, Nyusha, Vintage, Philipp Kirkorov, Vitas and Alsou. Music producers like Igor Krutoy, Maxim Fadeev, Ivan Shapovalov,[23] Igor Matvienko, and Konstantin Meladze control a major share of Russia's pop music market, in some ways continuing the Soviet style of artist management. On the other side, some independent acts such as Neoclubber use new-era promo tools[24] to avoid these old-fashioned Soviet ways of reaching their fans.[25] Russian girl trio Serebro are one of the most popular Russian acts to dominate charts outside of the European market. The group's most known single "Mama Lover" placed in the US Billboard Charts, becoming the first Russian act to chart since t.A.T.u.'s single " All About Us".[26]

Russian production companies, such as Hollywood World,[27] have collaborated with western music stars, creating a new, more globalized space for music.

The rock music scene has gradually evolved from the united movement into several different subgenres similar to those found in the West. There are youth pop rock and alternative rock (Mumiy Troll, Zemfira, Splean, Bi-2, Zveri). There are also punk rock, ska and grunge (Korol i Shut, Pilot, Leningrad, Distemper, Elisium). The heavy metal scene has grown substantially, with new bands playing power and progressive metal (Catharsis, Epidemia, Shadow Host, Mechanical Poet), and pagan metal (Arkona, Butterfly Temple, Temnozor).[28]

Rock music media has become prevalent in modern Russia.[citation needed] The most notable is Nashe Radio, which promotes classic rock and pop punk. Its Chart Dozen (Чартова дюжина) is the main rock chart in Russia,[29] and its Nashestvie rock festival attracts around 100,000 fans annually and was dubbed "Russian Woodstock" by the media.[30] Others include A-One TV channel, specializing in alternative music and hardcore. It has promoted bands like Amatory, Tracktor Bowling and Slot, and has awarded many of them with its Russian Alternative Music Prize.[citation needed] Radio Maximum broadcasts both Russian and western modern pop and rock.

Other types of music include folk rock (Melnitsa), trip hop (Linda) and reggae (Jah Division). Hip hop/rap is represented by Bad Balance, Kasta, Ligalize, Mnogotochie, KREC and others. An experimental rapcore scene is headlined by Dolphin and Kirpichi, while Moscow Death Brigade is a relevant techno /rap/punk band, well known for its stance against racism, sexism and homophobia. Other bands like Siberian Meat Grinder shares an experimental style of music.

A specific, exclusively Russian kind of music has emerged, which mixes criminal songs, bard and romance music. It is labelled "Russian chanson" (a neologism popularized by its main promoter, Radio Chanson). Its main artists include Mikhail Krug, Mikhail Shufutinsky, and Alexander Rosenbaum. With lyrics about daily life and society, and frequent romanticisation of the criminal underworld, chanson is especially popular among adult males of the lower social class.[31][32]

Electronic music in modern Russia is underdeveloped in comparison to other genres.[citation needed] This is mostly due to a lack of promotion.[33] There are some independent underground acts performing IDM, downtempo, house, trance and dark psytrance (including tracker music scene), and broadcasting their work via internet radio. They include Parasense, Fungus Funk, Kindzadza, Lesnikov-16, Yolochnye Igrushki, Messer Für Frau Müller and Zedd (Russian-German artist). Of the few artists that have broken through to the mainstream media, there are PPK[34] and DJ Groove,[35] that exploit Soviet movie soundtracks for their dance remixes. In the 2000s the Darkwave and Industrial scene, closely related to Goth subculture, has become prevalent, with such artists as Dvar, Otto Dix, Stillife, Theodor Bastard, Roman Rain, Shmeli and Biopsyhoz. Hardbass, an offshoot of UK Hard House originating in Russia in the late 1990s, has spread internationally via the internet, with acts such as Hard Bass School, & XS Project amassing significant followings.

The profile of classical or concert hall music has to a considerable degree been eclipsed by on one hand the rise of commercial popular music in Russia, and on the other its own lack of promotion since the collapse of the USSR.[36] Yet a number of composers born in the 1950s and later have made some impact, notably Leonid Desyatnikov, who became the first composer in decades to have a new opera commissioned by the Bolshoi Theatre (The Children of Rosenthal, 2005), and whose music has been championed by Gidon Kremer and Roman Mints. Meanwhile, Gubaidulina, amongst several former-Soviet composers of her generation, continues to maintain a high profile outside Russia composing several prestigious and well-received works including "In tempus praesens" (2007) for the violinist Anne-Sophie Mutter.

The early 2000s saw a boom of musicals in Russia. Notre-Dame de Paris, Nord-Ost, Roméo et Juliette, and We Will Rock You were constantly performed in Moscow theatres at the time. The popularity of musicals was hampered by the 2002 Moscow theater hostage crisis and was only revived at the end of the decade.

2010s saw the rise of popularity of Russian hip hop, especially rap battles on the internet by artists like Oxxxymiron and Gnoyny, among others.

Ethnic roots music

[edit]Russia today is a multi-ethnic state with over 100 ethnicities. Some of these ethnic groups has their own indigenous folk, sacred and in some cases art music, which can loosely be categorized together under the guise of ethnic roots music, or folk music. This category can further be broken down into folkloric (modern adaptations of folk material, and authentic presentations of ethnic music).

Adygea

[edit]In recent years, Adygea has seen the formation of a number of new musical institutions. These include two orchestras, one of which (Russkaya Udal) uses folk instruments, and a chamber music theater.

Adygea's national anthem was written by Iskhak Shumafovich Mashbash with music by Umar Khatsitsovich Tkhabisimov.

Altay

[edit]Altay is a Central Asian region, known for traditional epics and a number of folk instruments.

Bashkir

[edit]The first major study of Bashkir music appeared in 1897, when ethnographer Rybakov S.G. wrote Music and Songs of the Ural's Muslims and Studies of Their Way of Life. Later, Lebedinskiy L.N. collected numerous folk songs in Bashkortostan beginning in 1930. The 1968 foundation of the Ufa State Institute of Arts sponsored research in the field.

The kurai is the most important instrument in the Bashkir ensemble.

Buryatia

[edit]The Buryats of the far east is known for distinctive folk music which uses the two-stringed horsehead fiddle, or morin khuur. The style has no polyphony and has little melodic innovation. Narrative structures are very common, many of them long epics which claim to be the last song of a famous hero, such as in the "Last Song of Rinchin Dorzhin". Modern Buryat musicians include the band Uragsha, which uniquely combines Siberian and Russian language lyrics with rock and Buryat folk songs, and Namgar, who is firmly rooted in the folk tradition but also explores connections to other musical cultures.

Chechnya

[edit]Alongside the Chechen rebellion of the 1990s came a resurgence in Chechen national identity, of which music is a major part. People like Said Khachukayev became prominent promoting Chechen music.

The Chechen national anthem is said to be "Death or Freedom", an ancient song of uncertain origin.

In April 2024, it was reported that Minister of Culture Musa Dadayev had been instructed by head of Chechnya Ramzan Kadyrov to restrict music to specific tempos to "conform to the Chechen mentality and sense of rhythm" by 1 June, banning any vocal, musical, or choreographic works not composed between 80 and 116 beats per minute (BPM).[37][38] Dadayev later stated that this was meant to be guidance for the performance of traditional melodies, and was not meant to be an outright ban.[39]

Dagestan

[edit]Dagestan's most famous composer may be Gotfrid Hasanov, who is said to be the first professional composer from Dagestan. He wrote the first Dagestani opera, Khochbar, in 1945 and recorded a great deal of folk music from all the peoples of Dagestan.

Karelia

[edit]Karelians are Finnish, and so much of their music is the same as Finnish music. The Kalevala is a very important part of traditional music; it is a recitation of Finnish legends, and is considered an integral part of the Finnish folk identity.

The Karelian Folk Music Ensemble is a prominent folk group.

Ossetia

[edit]Ossetians are people of the Caucasian Region, and thus Ossetian music and dance[40] have similar themes to the music of Chechnya and the music of Dagestan.

Russia

[edit]

Archeology and direct evidence show a variety of musical instruments in ancient Russia. Authentic folk instruments include the Livenka (accordion) and woodwinds like zhaleika, svirel and kugikli, as well as numerous percussion instruments: buben, bubenci, kokshnik, korobochka, lozhki, rubel, treschyotka, vertushka and zvonchalka.[citation needed]

Chastushkas are a kind of Russian folk song with a long history. They are typically humorous or satiric.

During the 19th century, Count Uvarov led a campaign of national revival which initiated the first professional orchestra with traditional instruments, beginning with Vasily Andreyev, who used the balalaika in an orchestra late in the century.[citation needed] Just after the dawn of the 20th century, Mitrofan Pyatnitsky founded the Pyatnitsky Choir, which used rural peasant singers and traditional sounds.

Sakha

[edit]Shamanism remains an important cultural practice of the ethnic groups of Siberia and Sakhalin, where several dozen groups live. The Yakuts are the largest, and are known for their olonkho songs and the khomus, a jaw harp.

Tatarstan

[edit]Tatar folk music has rhythmic peculiarities and pentatonic intonation in common with nations of the Volga area, who are ethnically Finno-Ugric and Turkic. Singing girls, renowned for their subtlety and grace, are a prominent component of Tatar folk music. Instruments include the kubyz (violin), quray (flute) and talianka (accordion).

Tuva

[edit]Tuvan throat singing, or xoomii, is famous worldwide, primarily for its novelty. The style is highly unusual and foreign to most listeners, who typically find it inaccessible and amelodic. In throat singing, the natural harmonic resonances of the lips and mouth are tuned to select certain overtones. The style was first recorded by Ted Levin, who helped catalogue a number of different styles. These include borbannadir (which is compared to the sound of a flowing river), sygyt (similar to whistling), xoomii, chylandyk (likened to chirping crickets) and ezengileer (like a horse's trotting). Of particular international fame are the group Huun-Huur-Tu and master throat singer Kongar-ool Ondar.

Ukrainian music in Russia

[edit]Although Ukraine is an independent country since 1991, Ukrainians constitute the second-largest ethnic minority in Russia. The bandura is the most important and distinctive instrument of the Ukrainian folk tradition, and was used by court musicians in the various Tsarist courts. The kobzars, a kind of wandering performers who composed dumy, or folk epics.

Hardbass in Russia

[edit]Hardbass or hard bass (Russian: хардбасс, tr. hardbass, IPA: [xɐrdˈbas]) is a subgenre of electronic music which originated from Russia during the late 1990s, drawing inspiration from UK hard house, bouncy techno and hardstyle. Hardbass is characterized by its fast tempo (usually 150–175 BPM), donks, distinctive basslines (commonly known as "hard bounce"), distorted sounds, heavy kicks and occasional rapping. Hardbass has become a central stereotype of the gopnik subculture. In several European countries, so-called "hardbass scenes" have sprung up,[1] which are events related to the genre that involve multiple people dancing in public while masked, sometimes with moshing involved.

From 2015 onward, hardbass has also appeared as an Internet meme, depicting Slavic and Russian subcultures with the premiere of the video "Cheeki Breeki Hardbass Anthem", based on the S.T.A.L.K.E.R. series of games from GSC game world.[2]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ РУССКИЕ МУЗЫКАЛЬНЫЕ ИНСТРУМЕНТЫ [Russian Musical Instruments]. soros.novgorod.ru (in Russian).

- ^ Marina Ritzarev. Eighteenth-century Russian music. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., 2006. ISBN 0-7546-3466-3, ISBN 978-0-7546-3466-9

- ^ "Russian Music before Glinka". biu.ac.il.

- ^ "Интерфакты. Часть 6. Балалайка" [Interfacts. Part 6. Balalaika] (in Russian). Tomsk Regional State Philarmony. Archived from the original on 9 May 2018. Retrieved 6 June 2019.

- ^ "Почему Алексей Михайлович приказал сжечь все балалайки" [Why did Alexei Mikhailovich order to burn all the balalaikas] (in Russian). Cyrillitsa.ru. 7 December 2018. Retrieved 7 June 2019.

Everyone knows about the witch hunt of Inquisition times, but only few people aware that in 17th century Russia there were burning balalaikas for the same purpose

- ^ Holden, xxi; Maes, 14.

- ^ Frolova-Walker, New Grove (2001), 21:925

- ^ Maes, 14.

- ^ Bergamini, 175; Kovnatskaya, New Grove (2001), 22:116; Maes, 14.

- ^ Campbell, New Grove (2001), 10:3, Maes, 30.

- ^ Maes, 16.

- ^ a b Amy Nelson. Music for the Revolution: Musicians and Power in Early Soviet Russia. Penn State University Press, 2004. 346 pages. ISBN 978-0-271-02369-4

- ^ Soviet Music and Society under Lenin and Stalin: The Baton and Sickle. Edited by Neil Edmunds. Routledge, 2009. Pages: 264. ISBN 978-0-415-54620-1

- ^ a b "History of Rock Music in Russia :: Music :: Culture & Arts :: Russia-InfoCentre". russia-ic.com.

- ^ Walter Gerald Moss. A History Of Russia: Since 1855, Volume 2. Anthem Series on Russian, East European and Eurasian Studies. Anthem Press, 2004. 643 pages.

- ^ "David Oistrakh". The Musical Times. 115 (1582): 1071. December 1974. ISSN 0027-4666. JSTOR 960424.

- ^ Higgins, Charlotte (22 November 2000). "Perfect isn't good enough". The Guardian. Retrieved 7 July 2021.

- ^ Botstein, Leon (2006). "An Unforgettable Life in Music: Mstislav Rostropovich (1927–2007)". The Musical Quarterly. 89 (2/3). Oxford University Press: 153–163. doi:10.1093/musqtl/gdm001. JSTOR 25172838.

- ^ Goldsmith, Harris (October 1989). "Vladimir Horowitz at Eighty-Five". The Musical Times. 130 (1760): 601–603. doi:10.2307/965578. ISSN 0027-4666. JSTOR 965578.

- ^ Ballard, Lincoln Miles (September 2011). "Review of Sviatoslav Richter, Pianist". Notes. 68 (1). Music Library Association: 98–100. doi:10.1353/not.2011.0120. ISSN 0027-4380. JSTOR 23012874. S2CID 191336167.

- ^ "Emil Gilels". The Musical Times. 126 (1714): 747. December 1985. ISSN 0027-4666. JSTOR 965219.

- ^ Roffman, Frederick S. (September 1985). "Review of Galina: A Russian Story". Notes. 42 (1). Music Library Association: 44–46. doi:10.2307/898239. ISSN 0027-4380. JSTOR 898239.

- ^ Berger, Arion (3 October 2002). "Album Reviews T.A.T.U.: 200 KM/H In The Wrong Lane". Rolling Stone. No. 906. Archived from the original on 22 February 2008.

- ^ "Uncharted Territory: Pomplamoose Enters Top 10, Friendly Fires Debut". Billboard.

- ^ "Billboard – Music Charts, Music News, Artist Photo Gallery & Free Video". Billboard.

- ^ "Serebro". billboard.com.

- ^ "[.m] masterhost – профессиональный хостинг сайта(none)". www.hollywoodworld.org. Archived from the original on 29 March 2018. Retrieved 30 August 2018.

- ^ Diverse Genres of Modern Music in Russia Archived 7 July 2012 at the Wayback Machine – Russia-Channel.com

- ^ The Moscow News – Chartova Dyuzhina[permanent dead link]

- ^ "A Russian Woodstock: Rock and Roll and Revolution?; Not for This Generation".[dead link]

- ^ Modern Russian History in the Mirror of Criminal Song Archived 12 June 2008 at the Wayback Machine – An academic article

- ^ Notes From a Russian Musical Underground – A New York Times article about modern Russian Chanson

- ^ "44100hz ~ electronic music in Russia – Статья – Российская электронная музыка – общая ситуация". 44100.com.

- ^ "Russmus: ППК/PPK". russmus.net.

- ^ "DJ Groove". Far from Moscow.

- ^ See Richard Taruskin "Where is Russia's New Music?", reprinted in On Russian Music. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2009: p. 381

- ^ Treisman, Rachel (9 April 2024). "Chechnya is banning music that's too fast or slow. These songs wouldn't make the cut". NPR.

- ^ Oltermann, Philip (9 April 2024). "Chechnya bans dance music that is either too fast or too slow". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 21 April 2024.

- ^ Mchedlishvili, Luiza (15 April 2024). "Kadyrov says restrictions to music tempo were 'just recommendations'". OC Media. Retrieved 6 October 2024.

- ^ Ossetian music and dance on YouTube

Bibliography

[edit]- Bergamini, John, The Tragic Dynasty: A History of the Romanovs (New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons, 1969). Library of Congress Card Catalog Number 68-15498.

- Campbell, James Stuart, "Glinka, Mikhail Ivanovich". In The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, Second Edition (London: Macmillan, 2001), 29 vols., ed. Stanley Sadie. ISBN 0-333-60800-3.

- Frolova-Walker, Marina, "Russian Federation". In The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, Second Edition (London: Macmillan, 2001), 29 vols., ed. Stanley Sadie. ISBN 0-333-60800-3.

- Holden, Anthony, Tchaikovsky: A Biography (New York: Random House, 1995). ISBN 0-679-42006-1.

- Hosking, Geoffrey, Russia and the Russians: A History (Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2001). ISBN 0-674-00473-6.

- Kovnaskaya, Lyudmilla, "St Petersburg." In The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, Second Edition (London, Macmillan, 2001), 29 vols., ed. Stanley Sadie. ISBN 0-333-60800-3.

- Maes, Francis, tr. Arnold J. Pomerans and Erica Pomerans, A History of Russian Music: From Kamarinskaya to Babi Yar (Berkeley, Los Angeles and London: University of California Press, 2002). ISBN 0-520-21815-9.

- Most favorite American and Russian Music Artists (Dec 2018) (July 2020).

- Ritzarev, Marina, Eighteenth-Century Russian Music (Ashgate, 2006). ISBN 978-0-7546-3466-9.

- Ritzarev, Marina, Tchaikovsky's Pathétique and Russian Culture (Ashgate, 2014). ISBN 978-1-4724-2412-9.

Further reading

[edit]- Broughton, Simon and Didenko, Tatiana. "Music of the People". 2000. In Broughton, Simon and Ellingham, Mark with Mark, James and Duane, Orla (Ed.), World Music, Vol. 1: Africa, Europe and the Middle East, pp 248–254. Rough Guides Ltd, Penguin Books. ISBN 1-85828-636-0